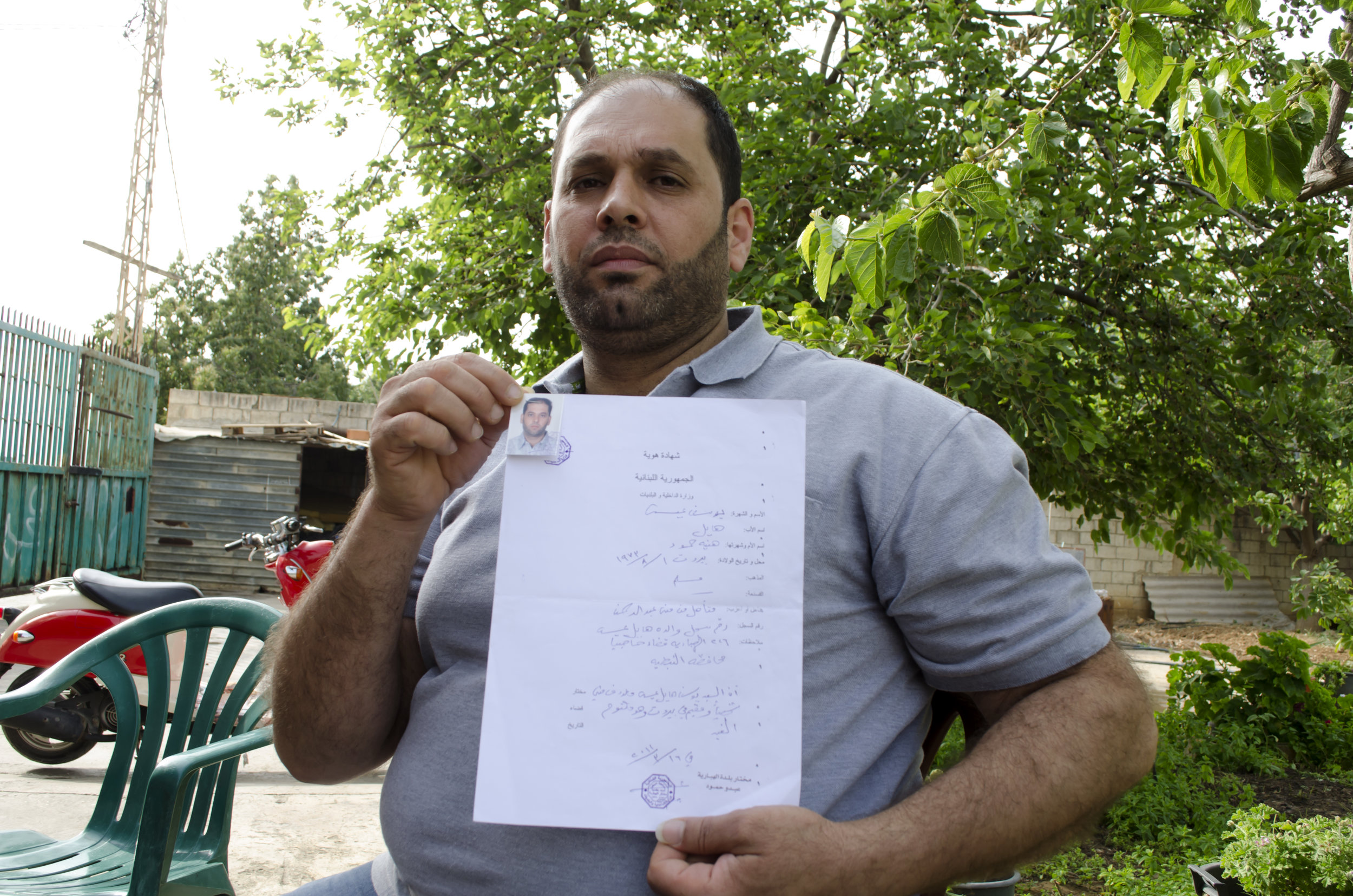

Youssef Issa and his family are Lebanese but stateless in the eye of the law. (The Daily Star/Antoine Abou-Diwan)

By Mat Nashed and Antoine Abou-Diwan

BEIRUT: Sitting outside his deceased mother’s home, Youssef Issa spoke about his grandfather with resignation. Though he never knew the man, he says he fled Lebanon to evade military conscription in 1932, a decision which has resulted in irreversible consequences for the ensuing generations of his family. That year, Lebanon was under a French mandate when it recorded its first and only demographic census. The outcome has preserved the cracks of a divided nation and its people. However, Issa’s grandfather was never counted. He had already left for Syria where he settled for a few years before returning to his village.

“He didn’t receive citizenship. He didn’t get citizenship in Lebanon or Syria,” Issa said. “My grandfather made mistakes and [now] we’re all paying for those mistakes.”

Eighty-four years later, Issa and his family are still struggling to prove their legal ties to Lebanon. They are not alone. Nearly 80,000 people are estimated to be stateless in the country, a figure which excludes the long-standing presence of Palestinian refugees and a growing number of Syrian children.

Citizenship 80 years ago didn’t have the same fundamental importance it does now: It was never needed to cross regional borders or to acquire basic state services.

Still, the way the world worked then doesn’t offer much solace to those deprived of citizenship today. According to rights groups, their ongoing predicament owes much to the unforgiving nationality laws in the country.

In Lebanon, citizenship can only be passed down through the paternal line of the family, a law that the government maintains will preserve the nation’s fragile sectarian balance.

Karima Chebbo, a lead campaigner with the Collective for Research & Training on Development and Action, a group pressuring to advance women’s rights in the Middle East, said that the government has tried to use the presence of Palestinian refugees to justify their stance.

They argue that more Palestinians could be permanently settled if Lebanese women were allowed to confer citizenship to their children – a scenario that many officials fear would tip the country’s confessional balance in favor of Sunnis.

“[We tell] the government that we are not talking about the case of Palestinian refugees. We are talking about our rights as Lebanese women. Palestine is another issue. We just want our rights,” she said.

Issa’s mother was Lebanese, meaning he would have citizenship if the law permitted women to pass nationality to their children, ending four generations of statelessness.

Lebanon is one of the seven worst countries in the world for safeguarding against statelessness according to the U.N. refugee agency, which also fears that the alarming number of Syrian children who have been born in the country risk growing up without a legal identity. And while Parliament has recently approved a law which grants citizenship to foreigners of Lebanese ancestry – under the condition that it’s traced from the paternal line of the family – the legislation does little to help people like Issa who have been born and raised on Lebanese territory.

There is little doubt that the Issas are from Lebanon. A handwritten document from the mukhtar of Hebbarieh – Issa’s ancestral village – attests to Issa’s identity and place of origin.

Youssef Issa shows a handwritten document from his village's mukhtar that attests to his identity and place of origin. But it is not proof of nationality in the eyes of the law. (The Daily Star/Antoine Abou-Diwan)

But in the eyes of the law, he and his family are not Lebanese. Without a nationality, he remains unable to own property, register his house or access basic health care. Issa even said that he had to use the identity card of another child to get his son medical treatment when he developed kidney problems as a baby. That’s because he had no identity papers except for an otherwise meaningless handwritten document from the mukhtar of Hebbarieh.

“They stop my son at the checkpoint whenever he walks home from school,” said Mona Issa, mother of Hadi. “He has a document from the mukhtar but the police don’t acknowledge it.”

Alice Karaze, a human rights lawyer to whom The Daily Star was referred to by the Social Affairs Ministry, said that officials were taking steps to prevent statelessness by communicating the importance of registering children to all their citizens.

However, when asked about parents who are unable to confer citizenship to their children since they don’t have it themselves, Karaze noted that safeguarding children from statelessness becomes much more difficult.

“In this case, these parents have to go to court to try to prove with the documents they have that they are indeed Lebanese,” she told The Daily Star. “The process can take a very long time. But they must prove in some way that their father is Lebanese. They even need to have a DNA test.”

Issa said that he has already pleaded his case to many political officials to no avail. Even if he was able to navigate the legal process, the fate of his family would still hinge on a single judge’s decision.

That wasn’t the case for 700 other people who were granted Lebanese citizenship in 2014 by way of a decree that was issued by former President Michel Sleiman at the end of his term. While 46 of those who received the nationally had been stateless, Chebbo insists that more children will grow up this way unless Lebanon grants women the fundamental rights they deserve.

“The problem is not with the people in this country. It’s with the law,” Chebbo said.

“If [our children] choose to remain in Lebanon ... we don’t want them to go through the same ordeal we went through,” Issa said.

Whatever is responsible for their dilemma matters little to Issa and his family, who are considering how to maneuver around it.

At the moment, they only have a travel document which differs from a passport since it doesn’t bear proof of citizenship.

The document enables Issa and his family to travel outside the country if they receive a visa, which is extremely difficult to obtain even for Lebanese nationals.

Nevertheless, Issa’s children still hold dreams for the future despite the obstacles ahead. Hadi wants to be a chef while his 12-year-old sister Riham hopes to become an Arabic teacher when she’s older.

Like any loving parent, Issa is trying to ensure that they live a better life than his own. How he’ll do that remains uncertain: It could entail pleading his case before a court or finding a way to apply for asylum in another country.

Those are his only options for as long as Lebanon’s nationality laws stay the same.

This story first appeared in The Daily Star, May 11, 2016.